Buyers of Tiger, Leopard, Jaguar & Lion Parts

At the 2010 International Tiger Conservation Forum a total of 13 “tiger range countries” participated in increasing wild tiger populations. Many of these nations have an interest in tigers and leopards both for their symbolism and in some cases due to the value of their parts. The trade in leopard skins, bones, and other body parts is particularly strong in several Asian nations where tiger skins and bones are popular. However sales to foreign tourists visiting Asia is not uncommon and large skins are highly valued in other markets including some parts of Europe and the Middle East (page 14).

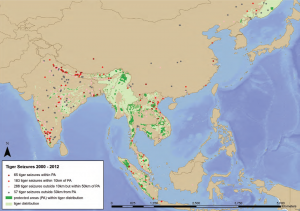

Tiger Seizures 2000-2012 (Asia). Source: WWF/TRAFFIC – Reduced to Skin and Bones Revisited, page 14.

Tiger Seizures 2000-2012 (Asia). Source: WWF/TRAFFIC – Reduced to Skin and Bones Revisited, page 14.

China’s trade in tiger parts officially ended in 1993 when it was banned by the government. However China and other nations continue to have numerous private farms and animal parks which may continue to be supplying tiger parts to restaurants or individuals as they had in the past when these parks acted as commercial suppliers of tiger skins and bones. In 1994 a growing popularity in tiger-bone gelatin, called cao, among tiger products sold in the North America suggested that its form made it easier to pass through Customs agencies (page 48) which were unable to detect the contents of the soap-like bar. During the 1990s much of the gel identified in Southeast Asian and international markets was produced in Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, Macau (pages 3, 48), and Vietnam (pages 49-50), all tiger range states. During this period the authenticity of some of China’s allegedly medicinal tiger products came under scrutiny by the users of folk medicine in many of these same countries (page 48). India, Nepal, Russia, Indonesia, China, and Cambodia are also listed as “major supplying markets” (page 3), but are not among a list of major entrepôts, throughout the 1990s.

In 2014 China publicly stated that trade in tiger skins would be allowed, but tiger bones would remain banned. Yet investigations performed over the past several years have shown that tiger parts continue to make their way from Myanmar (Burma) to China in growing numbers and Southeast Asia may be a fast-growing market. There were 535 seizures of tiger parts (page 15) by local law enforcement across Asia from January 2000 to April 2010. From 2010-2012 there were 61 live tigers seized from Southeast Asian smugglers (page 13).

In 2007 CITES determined that wild animals should not be farmed as a means of circumventing bans on international or domestic wildlife trade. However several nations are known to have tigers and leopards in captivity for commercial farming or tourist attractions in private parks even while wild populations experience high attrition rates due to poaching and capture for farming. Thailand had more than 1,100 tigers and leopards in captivity in 2013 (page 3) and in 2014 China was believed to have more than 5,000 tigers in captivity. Meanwhile Laos is home to small, commercial captive-breeding facilities as well as a transit nation for live tigers being smuggled from Southeast Asia to China (page 5). China’s “Wildlife Protection Law” may no longer include wording referring to captive-breeding and the medicinal use of wildlife parts, although this is disputed by independent translation, but the English version of the law presently provided by the government keeps the broad terms for the sale, breeding, domestication, and purchase of these animals for “special purposes” with proper approval or authorization.

There is also evidence of other countries harboring illegal big cat farms which support the demand from the Asian market for bones, skins, and claws. In Czech Republic an investigation begun in 2013 uncovered a crime ring run by Czechs and Vietnamese who were farming the parts of lions, pumas, and tigers. A series of raids called “Operation Trophy” were conducted and in July 2018 charges were brought against three individuals involved in the scheme.

Although an estimated 4,000 tigers survive in the wild today, they have long been kept as exotic pets, used in circuses, or in private zoos throughout the world with roughly 5,000 living in the United States. As of 2017, it’s estimated that China has a further 5,000-6,000 tigers in captivity.

Lions: Reviving the Big Cat Bone Trade

While wild tiger populations are believed to be continuing along a downward trend throughout most or all of the eight range states, Asian suppliers and practitioners of traditional folk medicine and exotic cuisine have sought other sources of bones believed to have similar properties. Although none of the alleged benefits of these medicines have been scientifically proven to be effective, legal and illegal enterprises have enjoyed success in marketing products with tiger meat or bones and have even used other cat bones as a substitute (pages 49-50). Private companies and wildlife traffickers have therefore sought to supply demand for tiger bones with the those of lions and leopards. Even the elusive snow leopard, a big cat genetically more closely related to the tiger than the leopard, has been found as an ingredient within the folk medicines manufactured by the pharmaceutical industry. However without formal regulations relating to these folk medicines, luxury foods, and charms, many of the existing products marketed to interested consumers are stimulating demand but are not believed to have any parts (page 37) from high-value wildlife at all.

Adopted in 1988 and subsequently revised many times, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife (also sometimes translated as “Wildlife Protection Law”) has been considered a means of supporting the domestic use and trade of wildlife and their parts. Although past amendments have removed references to medicinal uses and captive breeding of wildlife, Article 17 of the Protection of Wildlife presently states: “The state shall encourage the domestication and breeding of wildlife. Anyone who intends to domesticate and breed wildlife under special state protection shall obtain a license.” The Article does not specifically define the purpose of domestication or breeding, which has led to concern about the role of captive-breeding when medicinal and non-scientific uses of endangered species is not explicitly prohibited or regulated by the same law. Today, Article 22 is equally vague regarding the sale or purchase of species under special protections when the purpose falls under the broad categories of “scientific research, domestication and breeding, exhibition or other special purposes.” With few meaningful legislative measures taken to protect internationally- and nationally-recognized endangered species, conservation organizations continue to voice their concerns about inadequate steps by China and its supplying nations to curb both captive-breeding and illegal trade.

In July of 2017 the government of South Africa approved internally a decision long awaited by the nation’s captive breeding industry. This came after formal permission was given by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) that only lions sourced from breeders within South Africa would be permitted to be trafficked. A quota of 800 full lion skeletons was set to be exported “to Asia” with the clear, if unspoken, purpose of use in Chinese pharmaceutical companies’ traditional folk medicines. This occurred despite a small but statistically significant increase in reported lion poaching within South Africa’s national parks, on private land, as well as in sanctuaries after the announcement of consideration of a legal trade, but before the legal trade was granted by governing bodies. In 2018 the South African Department of Environmental Affairs increased the quota to 1,500 lion skeletons. Although claims have been made that farming these animals in captivity will satisfy demand, wild tigers throughout Asia and now wild lions throughout Africa continue to be illegally poached for international trade.

End-consumers of Tiger & Leopard Skins

Tiger and leopard skins can be sold as finished skins for home decoration or use in the creation of luxury carpets (page 2). Tiger skins can come from either the wild or from captive-breeding farms in Asia. In 2013 the Environmental Investigation Agency released a report that specified that within China the “primary consumers have been the business, military and political elite” (page 3). Tiger skins are also alleged to be used for purposes of graft in place of exchanging money.

In the 2000s a shipment of otter, tiger, and leopard skins worth $1.2 million were intercepted in Tibet (page 9-10), currently an autonomous region of China. Shipments like this were being trafficked from Nepal and India with the intent of being sold to Chinese, Taiwanese, and European tourists or were to be transported directly into China. However in a 2007 report published by TRAFFIC and the World Wildlife Fund interviews in Tibet suggested that there were people of all income levels that owned leopard and tiger skins (page 24). Some individuals even claimed to have clothing or ornamental garments made with big cat skins. The majority of respondents indicated that they owned skins not only because they were fashionable and were a way of showing off wealth, but also because they were used to make traditional costumes (page 27; also see The Tiger Skin Trail page 3).

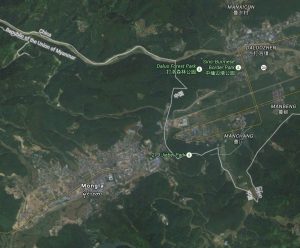

Mong La is a city in northern Burma, bordering China, known for gambling, prostitution, and the wildlife trade. It is easily accessible to Chinese tourists who were the primary buyers of rare wildlife parts in 2014. Prized big cat parts included tiger and leopard skins as well as tiger tails, which cost as much as 30,000 yuan ($4,890).

Commercial farming of leopards appears to be significantly less common than farming of tigers throughout Asia while poaching of wild leopards significantly out-paces tiger poaching (page 40). This is likely due to the larger populations of leopards across India and Southeast Asia compared to tigers.

In southern Africa many species are revered by traditional cultures for their powerful attributes and natural abilities. For those still following the ancient traditions of their culture the leopard skin has become an important symbol and a relatively recent fashion which over the past one hundred years has encouraged demand of ceremonial outfits made with leopard skins. This demand is estimated to have been the cause of 50,000 leopard deaths each year during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Efforts are currently underway to provide these groups with thousands of synthetic alternatives that will be more durable and much cheaper than a R4,500 ($530) skin from a real leopard.

End-consumers of Tiger Meat & Penis

In China tiger meat has become a fashionable delicacy, despite being illegal to consume. As early as 2005 restaurants were advertising “tiger” meat (page 37) and brought in customers through this gimmick, intentionally indicating that the alleged meat was not actually from a tiger. However there have been incidents of very wealthy people buying live tigers for private gatherings and having them prepared as a feast. In March 2014 it was reported that law enforcement in Guangdong province had arrested individuals who had smuggled in live tigers from Vietnam with the express purpose of selling their meat and bones for as much as ¥300,000 ($48,600) per tiger. The police also reported that they were aware of other incidents in previous years of real tiger meat being discreetly sold in the province.

Due to the cost-prohibitive price of tiger penis it may be that wealthy businessmen in Beijing and other cities with a growing upper class are the sole clientèle of restaurants selling tiger parts. In 2006 a dish that included tiger penis allegedly sold for $5,700 (£3,000) at a restaurant in Beijing. Like other animal parts that can command a high price tiger penis is sometimes faked. Typically horse, dog, or bull penis is sold as tiger penis (page 5) to unsuspecting consumers.

End-consumers of Tiger Bone Wine & Tiger, Leopard, and Lion Bones

Tiger bone wine is an alcoholic beverage that emerged as a traditional Chinese medicine with alleged health benefits. In recent years it may be more commonly used in more casual settings as a moderately expensive drink, like any other wine, but in 2005 was still being advertised as “medicinal wine.” Distributors of tiger bone wine also falsely claimed (page 31) that the bones came solely from animals that had died of natural causes, including fights with other tigers, and that proceeds were directed towards wildlife conservation.

In the 1990s known, comparatively major importers of tiger-bone medicines were: Belgium, Canada, Japan, Malaysia, and the United States (page 3), with Japan and the United States accounting for the largest quantity imported.

In late 2007 alleged tiger bone wine was sold by Qinhuangdao Wild Animal Park (page 3) directly to visitors for $83 per 250 ml bottle or $186 for 500 ml (16.9 oz.). While further investigations in 2012 revealed no tiger bone wine at the Qinhuangdao Wild Animal Park (page 16) they admitted to selling tiger skins. In 2012 Nanjing Pearl Spring Zoo was creating tiger bone wine for sale to Chinese government officials (page 13). In late 2011 a public sale of tiger bone wine on the internet was halted by Chinese authorities after pressure from conservation groups. But with little real enforcement of laws prohibiting trade in tiger parts the size of the market of both real and counterfeit tiger bone wine is unknown.

Tiger bones are also occasionally sold in a raw form for use in traditional Chinese medicine, but according to a report released in 2004 bones can be found in traditional Chinese medicines shipped to Asia, the United States, and Europe. In Vietnam’s historical usage of folk medicines tiger bone has been combined with other animal bones (pages 49 and 50) to balance the supposed characteristics imbued in tiger bones (pages 49 and 50), creating a more “medicinal” gelatin product. This resulted in a concoction of tiger-bear-monkey bones, but this is less common, if at all available today. Due to the comparative rarity of real tiger bones, the bones from other regional cats (page 50), including leopards and the unrelated leopard cat, as well as more distant wildlife such as snow leopards and most recently lions, are substituted. Yet these products are still called “tiger bone” cao (page 50).