Buyers of Rhino Horn

There are five existing species of rhinoceros: two that live in Africa (white rhino and black rhino) and three that live in Asia (Indian rhino, Javan rhino, Sumatran rhino). These species are further divided into four subspecies of black rhino, two of white rhino, one surviving subspecies of Javan, and three for the rare Sumatran rhino.

The two African species, as well as the Asian Sumatran species, each have two horns. The front horn is the largest and most prominent above the nose. The Indian and Javan species have a single horn, located above their nose. Male and female rhino of the same species have the same number of horns. These horns are primarily made of keratin, a fibrous protein and structural material also found in human skin, fingernails, bird beaks, porcupine quills, and the scales of the endangered pangolin.

Africa’s white rhino species is the largest of any living rhinoceros, weighing up to 3,600 kilograms (7,920 pounds), and is the continent’s third-largest species after the African bush elephant and African forest elephant. The black rhino, which is not actually black, can weigh up to 1,400 kg (3,100 pounds). Horns of the African rhino weigh on average 1.5-3.0 kilograms (3.3-6.6 pounds), with white rhino having the heaviest front horn which on average weighs 4.0 kilograms (8.8 pounds). Horns of the Asian rhino species are substantially smaller, averaging 0.27 kilograms (0.59 pounds) to 0.72 kilograms (1.58 pounds) (page 3).

Rhino Populations

Rhino horn has been highly prized by several cultures for over a thousand years and trade records suggest that the intercontinental trade in African rhino horn to the Far East has existed for centuries (pages 7-8). While rhinos have been killed in the past for their meat or solely for their skin (Run Rhino Run, page 79), from which shields were made, its horn is the most valuable product obtained. Other parts of their body have seen limited use as remedies in traditional Chinese medicine including dried blood, penis, and toenails (page 14).

As a result of both legal and illegal hunting both rhinoceros species in Africa have faced extinction before. With little or no hunting regulation in southern African nations during the 1800s the exceedingly common southern white rhinoceros subspecies was hunted nearly to extinction by European settlers, sport hunters, and opportunists cashing in on the rhino horn trade. The northern white rhinoceros subspecies, which once lived in Central Africa, had its numbers cut down dramatically by the early 1900s. By 1960 there were more than 2,000 individuals, however this population declined again during the following decades due to poaching. Today there are only three left. Black rhino populations also suffered from dramatic losses in countries like Kenya which saw its populations drop from an estimated 20,000 in 1960 to 330-530 (pages 5, 6).

Recent census estimates suggest that there are roughly 20,700 southern white rhino and 4,885 black rhino in Africa, however this may not factor in the more than 2,200 rhino lost in South Africa during 2013 and 2014, nor population growth since the census. It is thought that black rhino populations are trending upward, even while select populations continue to diminish. Of the Asian species, an estimated 3,333 greater one-horned rhino (Indian rhino) and only 58-61 Javan rhino are left in the wild, with official estimates of the Sumatran rhino at fewer than 100, but possibly as low as just 30 in the wild. The lifespan of a wild rhinoceros is unknown, but is expected to be 35-50 years for any African or Asian species. There is no known upper limit to a rhinoceros’ breeding age, however the mating “prime” range is thought to be 17-30 years old.

The International Rhino Horn Trade

Asia has been considered the leading consumer of rhino horn and other rhino parts for decades. However in the past 200 years many countries around the world have acted as major consumers of raw horn as well as carvings. With little or no hunting regulation in colonial African nations during the 1800s the exceedingly common southern white rhinoceros subspecies was hunted nearly to extinction by European settlers, sport hunters, and opportunists cashing in on the rhino horn trade. Simultaneously the southern white rhinoceros was being wiped out and by the end of the 1800s would be completely eradicated throughout its home range with the exception of a small, remote population in South Africa.

Among the most intense periods of rhino exploitation was from 1849-1895 when it was estimated that around 11,000 kilograms of rhino horn were exported from East Africa each year (page 6). This represents between 100,000 and 170,000 rhinoceros killed through the 47-year period (page 6). As the black rhino was the most common rhino species in that region (page 2) it’s likely that their populations took the largest toll. To supply the world’s demand East Africa had become the world’s dominant source and re-exporter of rhino horn.

Even Japan, whose imports during the early-mid 1880s came largely from Asian rhino species in Thailand and Indonesia, turned to buying African rhino horn by 1888 (page 11). India became a prominent supplier of Japan and India chose to sell the less expensive rhino horn from Africa rather and keep it’s Asian rhino horn for local Asian markets. From 1887 through 1903 officially imported more than 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) of rhino horn each year, with more than 2,200 kilograms (4,840 pounds) declared in 1897 and again in 1898 (page 11). This trend of buying African horn would continue for Japan, even as its suppliers changed, throughout the 1900s. By 1951 the country was the largest known consumer of rhino horn in Asia, averaging imports of 488 kilograms (1,073 pounds) each year through 1980 (page 11).

Little is known about historical black rhino populations, but in 1960 there were an estimated 100,000 black rhino in sub-Saharan Africa. Ten years later their population had decreased to an estimated 65,000 (page 4). From 1959-1974 the United States and the United Kingdom imported at least 2,642 kg and 1,686 kg, respectively (page 9). This was only a fraction of East Africa’s rhino horn exports during that period (page 8). A document recounting official Kenyan exports states that 28,570 kilograms (62,986 pounds) of rhino horn were legally exported from the country in the eight years from 1969 through 1976. Averaging 3.32 kg of horns per rhino this accounted for 8,585 northern white rhino and black rhino. About 8.5% of those exports occurred in 1976 alone.

Records of a 18 June, 1976 sale of 668 rhino horns weighing 985.9 kilograms showed an average price of 605.50 Kenyan Shillings ($87-105) per kilogram and $85,773-103,519 for all the pieces in the 9 lots. This sale, approved by the department Minister, significantly undercut both the retail and wholesale prices being asked for rhino horn abroad. The same document cites wholesale rhino horn prices in India as $375 per kilogram and a retail price of $875. Other discrepancies also came to light including a very limited number of buyers being invited to make bids and the winning bidder buying all lots in spite of not having the highest bid. Other lots were also sold at a fraction of wholesale prices and had their quality downgraded to reduce the reported worth of the rhino horn. Suspicious sales, open corruption at national and international levels, and virtually unchecked poaching had ushered in a “catastrophic” (page 27) period of poaching that was dubbed the “white gold rush.”

An Increasingly Illegal Trade

Almost every year from 1964 through 1971, with a surge in 1976, Aden and South Yemen were the largest importers of raw rhino horn exported from East Africa (page 8). While the legality of all of the horn is unknown, the rhino horn was either documented and officially exported from East African countries, officially imported by the Middle Eastern states, or both. This trade supplied Yemeni men with janbiya, traditional daggers that utilized cheap or exotic materials for their handles. From 1969 through 1977 an average of 3,235 kilograms of raw rhino horn was imported into North Yemen (page 9). In the years 1972 through 1978 North Yemen imported approximately 40% of the African horn on the world’s market (page 28). Rhino horn imports were banned by North Yemen in 1982, but small-scale trade continued until the 1990 unification (pages 9, 11) and even after Yemen’s Grand Mufti announced that it was unethical to kill rhinoceros under Islamic law (page 28). After unification Yemen’s imports of rhino horn may have increased over prior years (page 9), but it’s uncertain whether the country remained a significant importer as a result of economic impacts due to the Gulf War (1990-1991).

It’s estimated that the world market for rhino horn traded roughly 8,000 kilograms each year from 1970 through 1979 (page 9). The largest Asian importers during this period were Hong Kong (1,225 kg), China (1,025 kg), Japan (800 kg), Taiwan (580 kg), and South Korea (200 kg), accounting for an estimated 3,830 kilograms, or roughly 47% of the total world trade (page 9). Since customs records are incomplete (page 9), and the rhino horn trade was banned internationally during this period, it is likely that rhino horn was illegally imported to these and neighboring nations in addition to what is officially recorded.

The international commercial trade in African rhino parts was banned in 1977 when the two species were added to Appendix I of CITES (page 1). The Asian species had been listed on Appendix I in July of 1975 (page 1). The goal was to negatively impact demand for rhino horn and in turn allow rhino populations to recover, but this agreement did not affect domestic hunting or trade within nations and many rhino consuming countries did not take action to regulate trade. It wasn’t until 1993 that China officially banned rhino horn sales within its own borders. Rhino horn sale wasn’t prohibited by law in Vietnam until 2006. In many western nations laws are very specific in prohibiting imports of rhino horn unrelated to sports trophies, but less specific about the sale of rhino horn, and antiques containing rhino horn, within the country’s borders. In the United States new laws have caught Chinese nationals buying antique rhino horn and smuggling it into the Chinese market.

End-consumers of Rhino Horn Products

Whole rhinoceros horn is a material which has been used for special, traditional carved items in the Middle East and Asia. Records suggest that rhino parts were transported through the Middle East to China as far back as 2,000 years ago (page 7) and that these parts were used throughout the history of Imperial China. However it’s unknown whether rhino horn was specifically sought after during this period. It isn’t until as early as China’s Tang dynasty (618-907) that bowls and cups (page 7) made of Asian rhino horn were in use. China’s demand for rhino horn and carving of decorative items continued for the next thousand years (page 7), through the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), and became a statement of wealth for those who were able to afford to give such a luxurious item to the Chinese emperors on their birthday (Run, Rhino Run, page 53).

Due to availability, and possibly lower cost, researchers believe that items made of rhino horn during the Ming dynasty (1368-1643) were primarily made from African horn, brought to the East via long-established trade networks between East Africa and Asia (page 4). During the middle of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) the Pen-tsao Kang-mu (Compendium of Materia Medica) was written by Li Shizhen. This work became the most comprehensive text on flora, fauna, and minerals that were believed to have medicinal properties and includes information on the perceived properties of rhino horn. However it does not list rhino horn as a treatment for cancer.

It is unknown when other parts of the world began using goblets and cups crafted from rhino horn or when the legend emerged that poison would be neutralized when poured into such a container. Although certain alkaloid poisons are thought to react with the keratin and other proteins in rhino horn there is not enough evidence of this actually being used in the past to support the legend (pages 4, 5). But myths involving supernatural properties imbuing the horn of the rhinoceros would eventually penetrate a variety of cultures throughout the Middle East, Asia, and parts of Europe and North Africa (Run Rhino Run, page 54). Since then poison-detecting properties of the rhino have been mythologized and traditions among the wealthy have developed as a result. In the 1800s it was fashionable for wealthy North Africans to own one or more rhino horn cups (Run, Rhino Run, page 54). This may have contributed to the ornate, decorative cup carving industries in Ethiopia and Sudan that developed in the 1800s and persisted well into the 1900s (page 54). It was during this period that products partially utilizing rhino horn also became desirable decorative items in Europe (page 54).

Historically rhino carving has also existed in parts of India, Laos, Cambodia, China, and Japan. In China many small items, particularly clothing accessories, were carved from whole rhino horn (Run, Rhino Run, page 54). In Japan decorative netsuke, a type of fastener worn with traditional garments, were crafted from rhino horn as well as ivory, hardwoods, and other novel items (page 54). Ultimately rhino horn carving industries are not thought to have significantly contributed to a tradition or created demand by these cultures. Rhino horn’s popularity in Asia grew largely due to its perceived medicinal benefits (page 4).

The most expensive janbiya handles use high-quality polished rhino horn for the handle (page 7). These daggers have traditionally been used by Yemeni men as a status symbol since at least the 8th century (page 4) and janbiya made with a rhino horn hilt are notable for acquiring a sayfani (patina) with age, making it a prized family heirloom, and have value as a symbol of manhood. Less wealthy men must settle for a janbiya with a handle made of water buffalo horn, wood, or even plastic (page 96). One merchant who had a self-proclaimed monopoly on rhino horn imports alleged that he had imported 36,700 kilograms of rhino horn from 1970 through 1986 (page 28). The regional market may have peaked in the 1980s, when North Yemen was estimated to be importing roughly 40% of all rhino horn on the world market for use in janbiya (page 28) or to re-export to Chinese markets. During 1982 to 1986 North Yemen is believed to be one of the primary sources for more than 10,000 kilograms (22,000 pounds) of rhino horn imported by China (page 27). This horn would have been in the form of shavings and chippings leftover from carving the janbiya handle (page 27).

In 1979 in Taiwan and Hong Kong rhino horn from the Indian rhinoceros retailed for $18,000 per kilogram (page 4). In 1980 antique rhino horns carved in China were retailing in the United Kingdom for $900-5,000 ($2,628-14,600 in 2015 dollars). The reason for the disparity in prices is likely a result of the belief that rhino horn from Asia produced a much more potent effect, while the African rhino horn was weaker (page 26). This has historically contributed to greater demand for Asian rhino horn, but rhino horn from Africa has been in greater supply (page 25) for at least the last century.

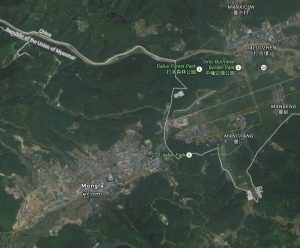

Whole rhino horn prices vary from shop to shop and from city to city. In 2014 the retail price of a whole rhino horn is commonly pegged at around $60,000 per kilogram, with some reports of as much as $100,000 per kilogram being charged. It’s unclear whether these higher prices are for carved or ornate rhino horn, finely polished and with gold accents or jewels. But independent investigations have turned up other retail prices straight from Asia. In Southeast Asia’s notorious wildlife trafficking city of Mong La, Burma a shop owner quoted $45,000 for an entire rhino horn which was likely from an Asian rhino due to its small size. Chinese frequently visit Mong La, a short distance from the country’s border, and are said to be frequently the buyers of expensive and illegal items including tiger skins.

In Europe and the United States antique rhino horn walking canes from pre-Great Depression era England are readily available from prestigious auction houses. Antique cups are also highly valued and are still legally sold in some parts of Europe and North America, however some illegal traffickers have used this as a means of procuring rhino horn for the Chinese market. Similar concerns were expressed in September of 2010 by the United Kingdom’s Animal Health after the agency reported a rise in sales of antique rhino horn products. Some customs agencies have policies implemented to racially profile individuals likely to be rhino horn traffickers.

End-consumers of Powdered Rhino Horn, Organs, & Urine

The rhino horn trade from Africa to the Middle East, and to Asia, has existed for centuries (pages 7, 8). But the myth that rhino horn can cure cancer is new. While the earliest recorded usage of rhino horn as a medicine dates back more than 2,100 years to the writing of the Shénnóng Běncǎo Jīng (The Classic of Herbal Medicine) there is no documented evidence that rhino horn can treat cancer in western medicine nor is there mention of it in Traditional Chinese medicine or Southeast Asian folk medicine. But myths persist about the way rhino horn has been used in specific cultures.

A common myth known by westerners is that powered rhino horn has been used as an aphrodisiac in Southeast Asia, but mostly this is re-reported by news media without sources. Undercover investigation reported in Run, Rhino, Run (Martin and Martin, 1985) showed that there is also no evidence of rhino horn being prescribed as an aphrodisiac in Chinese traditional medicine books (page 71), nor any pharmacists selling rhino horn for that purpose. However there is historical evidence of powdered rhino horn being used as an aphrodisiac by some people in India. The Gujarati people may have believed that powdered rhino horn could work as an aphrodisiac (page 4), but its use likely ended (page 25) in the late 1980s or early 1990s when supply of rhino horn decreased and the price skyrocketed, causing social customs to change (page 27).

In traditional Chinese medicine powdered horn is typically prescribed for the reduction of high fevers (page 8). This alleged remedy likely motivated and shaped rhino horn usage in surrounding countries, where rhino horn is similarly prescribed. Shavings and powdered rhino horn, as well as rhino blood, urine, and skin, have been used as traditional medicines by Asian cultures including the Burmese, Chinese, Nepalese, South Koreans, and Thai (page 4). South Korea and Thailand were the largest importers (page 14) of rhino horn during the 1970s and into the 1980s, largely for its alleged medicinal purposes (page 29). In post-war Japan pharmacists had prescribed medicines with rhino horn as a purported ingredient, but by the 1980s after joining CITES pharmacists were suggesting horn from other animals as an alternative, like the now critically endangered saiga antelope. In the latter half of the 1900s China has been a major manufacturer (page 10) of medicines (page 13) allegedly using rhino horn as an ingredient (page 10) despite national and international bans. China has exported pills, tonics, and other forms of these medicines to Hong Kong, Japan, Macao, Philippines, and South Korea (page 10).

In late 2011 prices for powdered rhino horn varied between $33 and $133 per gram in Vietnam. But a booming economy and one of the lowest unemployment rates in the world has led to a growing middle class and increased consumer spending. Renewed interest in traditional folk medicine and Traditional Chinese medicines are gaining popularity in some areas and may be contributing to demand for real rhino horn as well as related products. Today Vietnam is thought to be the largest consumer of rhino horn, but independent investigations suggest that rhino horn is becoming harder to find in the shops and market stalls in Hanoi, Vietnam due to strict penalties put in place in 2006 and decreasing consumer demand for folk medicines. In May of 2015 the Director of the Vietnam Management Authority for CITES, Do Quang Tung, claimed that Vietnamese demand for rhino horn had dropped 77% from the previous year.

Historical End-consumers of Rhino Skin

Rhino skins have been found in markets in Hong Kong and Brunei alongside other rhino parts with purported medicinal value. In 1982 dried rhino hide retailed for around $370 per kilogram and for $635 per kilogram in Singapore (page 11). In the late 1980s and early 1990s Bangkok, Thailand had among the largest quantity of rhino parts for sale in traditional medicine shops, from both African and Asian sources (page 14). These parts included dried blood, horn, penis, sections of skin, and toenails (page 14).

According to the book Run, Rhino, Run the skins of rhinoceros have been used for many purposes among some African and Indian cultures. Ornate and ornamental shields made with rhino hide and gilded in gold were created in India during the early 1700s (pages 76, 77, 81). Unornamented shields were kept by Ethiopian aristocrats of the 1800s and also used by mercenary warriors fighting for Sayyid Majid bin Said Al-Busaid, the first Sultan of Zanzibar (page 76). During the same period, and through the early 1900s, some whips made for use on livestock and humans were created from rhino skin (page 76). Ornate and decorative shields made with rhino hide and gilded in gold were also created in India during the early 1700s (pages 76, 77, 81).