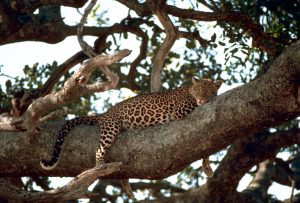

Leopard Profile (Panthera pardus)

The leopard is one of five existing species in the Panthera, “big cat,” genus which also includes the lion, jaguar, tiger, and snow leopard. Leopards are considered a keystone species, a creature that has a disproportionately large impact on its local environment. It is one of Africa’s and Asia’s most well-known and successful feline predators and is very similar to the jaguar that is native to parts of Central and South America. However the two species have not historically inhabited similar ranges, instead it’s thought that jaguars and leopards descended from a common ancestor which no longer exists, but found success in all the ranges that these two species currently inhabit. The leopard is not closely related to the cheetah, although it presently and historically inhabits a similar range and leopards are often mistaken for cheetah.

Leopards are a single species with the binomial name Panthera pardus, but have nine known subspecies that are currently recognized, though only one of these subspecies is currently present in central and southern Africa. The other eight range throughout parts of east Asia and parts of the south Pacific; the Indian sub-continent; and select regions of Central Asia and the Middle East, however it is increasingly rare in the Arabian Peninsula and highlands of Iraq and Iran. As a species the leopard is well suited to nearly any environment across the Old World and they can be found in lowveld forests, bushveld, grassland, mountains, and exteriors of deserts. The clouded leopard, native to southeast Asia, and the Sunda clouded leopard of Sumatra and Borneo in the South Pacific are not closely related to leopards or any big cat species despite their similar appearance to leopards.

Leopards are among the most solitary cat species and spend a substantial portion of their lives alone. Most of their interaction with other leopards comes during patrols of a leopard’s territory which have been observed being up to 78 square kilometers (30 square miles) and may be even larger in areas with low habitat quality. A territorial male can come into contact with one or more females in overlapping ranges or a male looking to establish his own territory, but otherwise they will avoid contact. Females will raise their cubs and teach them to hunt without the male present. At 18-24 months of age the subadults will be experienced enough to go out on their own.

As a result of their solitary nature adult leopards will typically hunt by using a combination of stealthy ambushes and immense strength to catch prey as much as five times its own size. Its intricate spots and spot groupings on its body, called “rosettes,” give it impeccable camouflage. Clever tactics, patience, and remarkable camouflage has earned the leopard the nickname “prince of stealth.” This contrasts sharply with the cheetah which may use stealth or openly stalk its prey before sprinting at over 100 kph (62 mph) to catch it.

Leopards are incredibly strong for their size and are capable of taking down prey roughly three times their own size, up to 270 kg (600 pounds). They are also very good climbers and in some cases will drag all or part of a carcass up a tree, called caching, to protect it from being stolen by competing predators.

ENVIRONMENTAL ROLE

An essential species in maintaining a balanced ecosystem, leopards can hunt in many different types of terrain and vegetation while highly specialized species like the cheetah are limited to hunting in areas where they can use their high speeds (page 2). Leopards and lions are known to adapt their prey preferences based on seasonal availability, while cheetah are not (page 5). Leopards in West African forests have also been documented as having personalized prey preferences (page 197), which suggests that leopards in different habitats impact local ecosystems differently.

Their ability to live and hunt in many different environments, along with having a less specialized diet, gives an advantage when it comes to competing for food. However leopards may not be lacking in environment- or hunting-specialization as previously thought (page 8); they are simply better suited for a wider variety of environments and can hunt a wider variety of prey than other animals with documented specializations. Leopards are known to prey on a variety of antelope species and will also eat some of the smaller primate species including baboons and vervet monkeys.

THREATS & POACHING

The leopard may not be considered an apex predator due to fierce competition where they share a habitat with tigers in Asia and with lions primarily in Africa. Tigers can be 150-300% the size of a leopard and lions can be 100-200% the size of a leopard and will persecute those within their range to reduce competition for food. One or more spotted hyena may also work to steal a leopard’s kill or attack it outright while in some areas the smaller brown hyena is known to scare individual leopards from their kills. While predator persecution accounts for a large number of natural leopard deaths, human-related factors including habitat destruction, human-wildlife conflict, and poaching are dramatically impacting the populations of leopards even in protected areas.

Despite having among the largest distributions of any cat species, today the leopard occupies at most 37% of its historical range (page 8) worldwide and the Arabian, North-Chinese, and Amur subspecies occupy as little as 2% (page 10). Leopard subspecies in Africa are believed to have lost at least 36% of their historical range (page 52) while the cheetah has lost 76.5% and the African lion more than 82%. Along with their habitat, leopards are declining in numbers. Fewer than 200 leopards are estimated to remain in the Arabian peninsula and are likely extinct on the island of Zanzibar.

The leopard is considered the most persecuted large cat species in the world as well as among the most highly sought after by hunters (page 2). The rosettes and spots on a leopard are primary factors in the desirability of the animal’s skin by humans. It has become a status symbol throughout many cultures of the world reflecting past traditions and modern wealth. Leopard skin ornamental clothing is coveted by people from Tibet to South Africa and leopard skin rugs or wall-hangings are also popular throughout Southeast Asia and many parts of the world.

Read more on Buyers of Tiger and Leopard Parts ►

Due in part to the difficulty in identifying subadult males from females there is concern that historic trophy hunting in Tanzania has resulted in an unsustainable number of accidental shootings of females which may have impacted current population levels (Spong 2000, 2002) even in countries like where hunting females is banned (page 3). Meanwhile a few countries, such as South Africa, have historically allowed the hunting of female leopards (page 7), the impact of which has gone undocumented. These practices have the potential to effect the long-term availability of leopards in regions with legal hunting and is further stressed by poaching and private and communal land owners in South Africa (page 4) who illegally kill “nuisance” leopards on their property.

The usage of leopard-hunting permits across Africa attempts to regulate populations by allowing a specific number of leopards to be killed each year according to a quota. In 2008 African nations were permitted (page 2) through international agreement the export of 2,648 leopard skins from trophy hunting. However regulating bodies in South Africa and other nations have routinely failed to adequately estimate the impact of hunting in regions where hunting licenses are being reserved. There is also a paucity of research into the exact number of leopards in regions throughout Africa and Asia and whether those local populations are increasing or decreasing. These factors can result in trophy hunting permits being distributed without regard to leopard population density, wildlife management, or the long-term effect of the removal of these animals from the ecosystem. This likely encourages private hunting reserves to stock high value wildlife from breeders and wildlife sellers with animals of dubious origin (some illegally take cubs from the wild) and allows the blame of population decline to fall on the licensed hunters because all hunting becomes potentially unsustainable through mismanagement.

CONSERVATION

A large number of groups focusing on the conservation of wild cats or big cat species have been created to study existing populations, preserve and protect endangered species and their habitat. They also inform governmental agencies how to protect endangered species through legislation, on the ground action, identify trafficking vectors, and how to assist humans living in areas where they come into contact with protected or dangerous wildlife species.

There are also efforts underway to assist small communities who have leopards and other large predators living nearby. One of the goals is to reduce human-wildlife conflict by providing basic shelter for livestock that are at risk of predation by these carnivores. Some groups also provide predator compensation for livestock that are lost to local predatory wildlife, thereby reducing the desire for retaliatory killings of lions and leopards and also making sure that pastoral people dependent upon livestock are still able to run a successful business. Providing synthetic materials as an alternative to real leopard skin for ceremonial uses is also having a positive effect on leopard conservation.

Additional Print Sources:

“The Safari Companion: A Guide to Watching African Mammals” Revised Edition, by Richard D. Estes (Copyright 1999 by Chelsea Green Publishing Co.)

“Walker’s Mammals of the Modern World” Sixth Edition, Volume 1, by Ronald M. Nowak (Copyright 1999 by The Johns Hopkins University Press)